It was rewarding to see Nancy Holt, mythic figure and important artist for me. Her brief comments on her and Robert Smithson’s experience building "Spiral Jetty" were remarkable and enjoyable- no scholar with brainy theories can match the appeal of an artist talking about how he or she created a piece. Nancy Holt’s presence and words carry and transmit that closeness -artistic and personal- she had and shared with Robert Smithson. Being there listening to her talking about “Bob” and his death, and how she and Richard Serra and Tony Shafrazi built “Amarillo Ramp” I could almost feel the pain of Smithson’s tragedy and sense his absence.

But at the same time, I expected more from her than just showing slides of Smithson’s work and saying the name and location. Her speech seemed to be slow and laborious to deliver, improper of an eloquent artist author of the classic “Sun Tunnels” and other astronomy- and geology-related complex installations, accompanied by essays in some cases. Perhaps she’s just public-shy?

She was nevertheless natural and funny- it was intimate and emotional to listen to her story of “Bob and Nancy looking in The New York Times for buying an island with purposes of creating 0 on it”. Smithson was fascinated with islands and water (his “Floating Island” is a developed example of this). Nancy Holt bought an island of off the Maine coast –she still owns it-, but when they saw their property it was too beautiful for her husband, and he couldn’t create on it. Smithson needed a barren, uninteresting space.

Nancy Holt did present a clear idea on Robert Smithson’s long-discussed earthworks’ conservation. Rebuild or let nature act? Keep or let it go? I cannot conceive any doubts about the issue, for she doubtlessly expressed her vision, that of Smithson himself: PRESERVE.

She proudly showed an extended series of the “Spiral Hill” and “Broken Circle” earthworks in Emmen, The Netherlands (1971), explaining how the community cares for them, the owner of the mine where they were built loves them and the two works have been repeatedly reinforced and preserved in order to keep them visible, against water damage.

A slideshow of “Amarillo Ramp” showed its dramatic change, from a solid tail of earth to a minimally-arising line of overgrown soil. Nancy Holt’s words on how Stanley Marsh (the owner of the ranch where the earthwork was built, not mentioned by her) drained the entire Tecovas Lake (and it’s been dry ever since) to allow Holt, Serra and Shafrazi building the piece were proof of the dedication of Marsh and other business people to help create non-orthodox art by outsiders like Smithson and Michael Heizer.

But -above all- the slides helped Nancy Holt point the way “Amarillo Ramp” has being cared for, controlling the growing weeds and tiding the site. She also defended the sometimes-discussed fact of being the earthwork in Amarillo an idea of Smithson but an actual construction of her wife and friends after his untimely death. Nancy Holt said, reasonably, that it is as much a creation of Robert Smithson as any other piece, for he had fully developed the project and “only” the making it real was lacking. If we consider “Floating Island” a Smithson artwork, or all those sand-stone-and-mirror sculptures recreated in museums and galleries after his death, there is no reason for denying the originality and fully attribution of “Amarillo Ramp” to Robert Smithson himself.

Furthermore, and despite her not having mentioned the “Spiral Jetty” preservation/rebuilding delicate issue, she closed her intervention by reading “morceaux choisis d’apres” (chosen fragments from) the Moira Roth-Robert Smithson conversation published on the recent “Robert Smithson” retrospective catalogue. And what she read was and is meaningful and decisive, although it did seem to impact nobody:

“I was never interested in works without substantial permanence, you might say. I wanted works that would have a longer duration”.

“Robert Morris attempted to build his Observatory, which has since disintegrated. But the Broken Circle and Spiral Hill are still there in their new condition... The ground cover is now growing on the hill, and Broken Circle has been reinforced.”

(Asked about preservation), “What do you mean? Just let it…”. “No, I’m not interested in that. The effects of erosion I don’t find especially edifying”.

“So I’m interested in something substantial enough... something that can be permeated with change and different conditions”.

Solid and substantial, meant to last long although naturally affected by changes. Robert Smithson wanted his works to endure.

Shouldn’t these paragraphs suffice to demonstrate Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt’s advocacy for the preservation of his earthworks? Whereas “Broken Circle-Spiral Hill” and “Amarillo Ramp” have been protected to guaranty conservation arising no protests, why is “Spiral Jetty” such an issue?

***

The restoration-reinforcement of Robert Smithson’s earthworks was virtually the only point of interest derived from the symposium (I admit we left after the first session, fretting and cussing). What was supposed to be a discussion between scholars and Nancy Holt turned to be a “let me read my prepared essay with no spontaneity and cause mental weariness to you all”. “Public” was not the word for this event, since the authors did nothing else than clumsily reciting their papers and leave. “No time for questions, sorry”. For the people this was not, just a self-celebration of braininess.

Ann Reynolds showed once again her well-deserved position as “most deadly tedious scholar in America” offering an opaque discourse on I-don’t-have-a-clue-something about “The dematerialization of the artwork” with no slides and without moving from her seat- straight, no water. Like her Robert Smithson book, 500 pages of dry indecipherable theory. And that’s it- I’m Ann Reynolds, happy to meet myself!

She did mention, though, the “disappointment” one feels (I felt) upon arriving to the Jetty, promptly substituted by feelings of unfamiliarity with the awkward environments and everything it entails. Conversely, it was proof of how locked upon herself Ann Reynolds may live that she didn’t know “Spiral Jetty” has been washed out of his salt crust, showing now the original black tone of the basalt rocks. This is a notice that popped out in the national media last May, even in the front page of Yahoo News!.

The evolution of the “Jetty”, its constant changes and colors was Hikmet Loe’s contribution to the general dullness of the symposium. Living in Salt Lake City and studying the “Jetty” continuously she knows better than anybody else about how the work looks day after day, first-hand. But she preferred to throw upon us yet another mortally dull read paper, no imagination left.

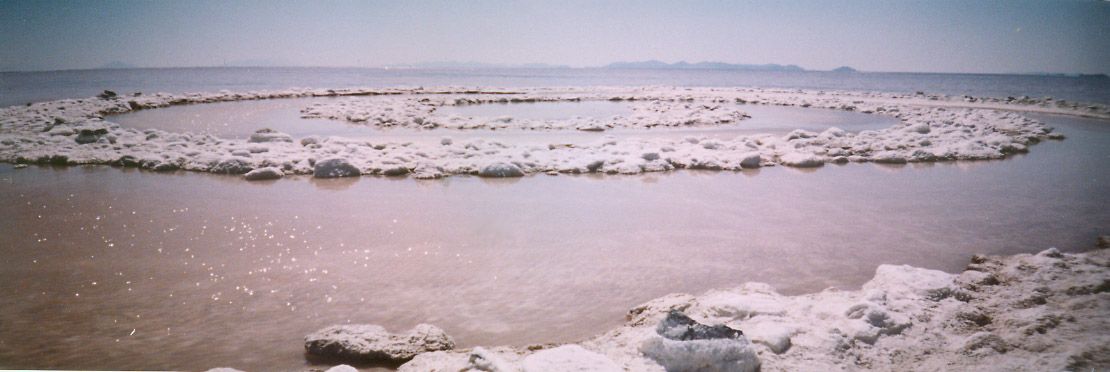

I did agree with her, though, and shared the feeling of how “"Spiral Jetty" is shaped by your experience”. We could say there are as many Spiral Jettys as visitors to it, for our being there and our perception of the piece are an integral part of the work, probably much more than the famous video some say is the work. The physicality of the experience in Great Salt Lake, the weird lunar landscape, the journey to Rozel Point- they’re all part of the work. The video is just a compressed taped statement of all that, shown in a gallery.

Reflecting on this, Robert Smithson said in his 1973 interview with Moira Roth:

“That’s a work (Spiral Jetty) that’s very much involved with the processes of nature insofar as it goes through all different kinds of climates, dates and seasonal states. It’s involved with a kind of ongoing process. It’s very much in the actual landscape”.

A video shot in a specific time and situation will never reflect the constant changes “Spiral Jetty” has gone through after 1970. Thus, the movie is only a reliquary of a dated time and place. Watching the reel will never ever substitute or be equaled to witnessing and living the "Jetty" in the landscape. Those taped images shown in museums around the world may only be an aesthetically rich but frustratingly incomplete, aseptic substitute; a physically dead remedy for those who will never experience the apocalyptic visions of Great Salt Lake. A reproduction of an original very much fitting with its/our times, where time and landscape cannot be transmitted.

As for the “Jetty” being shaped by our own experience, Robert Smithson himself again in the 1973 interview with Moira Roth acknowledged his considering the different views of the piece:

“How the public views the land has to be considered too. In other words, this isn’t a private, cult thing. When you get out to a place like Utah you’re not dealing with rarefied mentalities. One has to consider the ordinary view of the landscape as well as the more cultivated”.

For “Spiral Jetty” is famous in part due to this dichotomy of receptions: scholars and rednecks alike flock to the Great Salt Lake to experience what is probably the most famous (or widest-reaching) artwork of the Twentieth Century. Some know (or think they know) everything about its creation and meaning, others –locals- have just read about in their town press and are curious. Some will walk down and feel the “Jetty”, some will stay on the SUV and drink a beer. Smithson thought about all of them. He created a democratic artwork linked to his interest with Frederick Law Olmsted and Central Park as “a landscape for all”. Unlike many of his peer artists and critics of the Sixties and Seventies, he was not interested in Communism, as he remarked in the aforementioned 1973 interview with Moira Roth.

Robert Smithson was intellectually thick and opaque, probably boring, but at least his “heap of language” was meant to be “matter and not ideas”, “printed matter” with “a kind of physical presence”. A stack of words forming an earthwork, perhaps with no meaning. This separates and differentiates his dullness from that of Ann Reynolds and other famously irksome Smithson scholars who actually care and give grand meaning to their unattainably dreadful heaps of impossible language (would this mean that Smithson didn’t take himself serious? Hard to believe).

***

Another one of Hikmet Loe’s thoughts that caught my attention was her saying “"Spiral Jetty" offers an experience of the land and of ourselves”. Being in an isolated corner of the Great Salt Lake surrounded by desert and mountains will, as do the other Earthworks in Nevada and Utah and any desert landscape of the American West, make us aware of ourselves and our being in the place, in the Nature. We become self-conscious of our being human in an expansive, seemingly infinite environment that overwhelms our senses.

A visit to “Spiral Jetty” is a visit to the landscape of the American West, and ultimately a visit to our inner selves.

***

The Robert Smithson Symposium in New York City, September 24 2005 was a tremendously arid heap of language. Bob would have liked it that way.